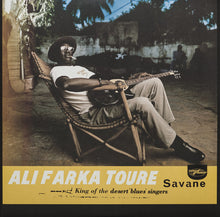

Ali Farka Touré was one of the true giants of African music, the greatest ambassador of desert blues, and a consummate performer and composer. Amazing, then, that he did not even see music as his central life’s work. That, he felt, was working the land and tending to his family. He held true to this belief strongly, spending most of the last decade of his life in his northern Mali hometown of Niafunké and “retiring” from the spotlight more times than Roger Clemens. He was elected mayor of Niafunké in 2004, and claimed he’d only return to music if duly inspired.

It was around that same time he was diagnosed with terminal bone cancer, against which he’d struggle for his final two years. Somewhere in that fight against disease, he found inspiration, and channeled it into his final work, a collaboration with kora player Toumani Diabate (In the Heart of the Moon) and Savane, recorded simultaneously by longtime Touré producer Nick Gold at Bamako’s Mandé Hotel. In the Heart of the Moon won him his second Grammy just weeks before his death, while Savane stands as his posthumous defining statement, a deeply felt album that stands among his best.

The album flows like a river, at times, tumultuous, at others placid, but always full of life and movement. Mixing his instantly identifiable electric guitar sound with a band that includes bamboo flute, ngoni (a four-stringed lute), traditional percussion instruments and a one-stringed violin called an njarka (all of which Touré himself played well), he conjures an elemental thrum on Savane as organic as the soil of his farm. Harmonica and saxophone make cameos, and Touré’s raw, powerful voice is answered by understated chants and choral vocals.

Album opener “Erdi” is a mesmerizing swirl of American and African blues, matching hypnotic rhythms with scorching blues harp and ragged guitars. The music is intense and sharply focused, and Touré sings as though in a trance. Surely he was aware that these were the last notes he would commit to tape, and he makes them count. Touré spoke seven regional languages, and this album bestrides the music associated with all of them, especially his own Sonrai people and the Kel Tamashek, better known as the Tuareg, of extreme northern Mali. It seems that modern Saharan bands like Tinariwen and Etran Finitawa learned much from Touré.

One of the most powerhouse performances of Touré’s entire long career comes on the remarkable title track, a song that capitalizes on the contrast between restraint and baroque flourish. The rhythm is simple, repetitive, and quiet, just a few chords played on guitar, and Touré’s raspy vocal is similarly controlled. Meanwhile, his focused electric guitar solos spar with a wild, almost totally unchecked kora part.

Touré was never supposed to be a musician-- his noble lineage discouraged it-- but he claimed that he was drawn to its power, and so became a musician by calling. On Savane, his final recordings demonstrate how well he was able to wield that power. It is beautiful, emotive music, literally and figuratively entrancing. Touré may be gone, but on this album you get the sense that he is still very much with us, and that his spirit is in no danger of fading.

PITCHFORK